Find Coherence (Part 4)

A Guide to Political Judgment in Fractured Times (5-part series)

Part 4: Putting It All Together —Judgment Under Fire

This is Part 4 of “Finding Coherence: A Guide to Political Judgment in Fractured Times.” Part 1 diagnosed why political judgment has become so difficult. Part 2 made the case that conflict itself isn’t the problem—productive contestation is how democracies work. Part 3 gave you four types of political conflict and how to distinguish them.

When a story breaks you feel it immediately. Anger, vindication, fear, that absolute certainty you know what’s happening and what it means.

That feeling is real. But it’s not judgment. It’s the starting line.

Pause. Everything depends on that one move.

What This Framework Actually Assumes

Before going further, let’s be honest about what this approach takes for granted:

It assumes evidence and expertise matter. If you think all experts are compromised or that your gut feeling equals their research, this won’t work for you.

It assumes the Constitution is legitimate and can self-correct. If you think the Constitution was designed by wealthy elites to protect their power and needs replacing, not reforming, you’ll need a different framework.

It assumes good-faith disagreement is possible. If you’re certain the other side is acting in pure bad faith — lying, grifting, knowingly spreading propaganda — then treating their concerns as potentially legitimate will feel like collaboration with evil.

It assumes you have time and distance. This process requires pause, reflection, synthesis. If you’re living paycheck to paycheck, if politics directly threatens your family, if you don’t have the luxury of “let me think about this,” then telling you to pause and consider multiple perspectives sounds like privilege talking.

These aren’t neutral assumptions. They’re liberal assumptions in the broad sense — faith that we can reason together, that institutions can work, that evidence can settle some disputes, that incremental progress through negotiation beats revolution or paralysis.

If you reject these assumptions, you’ll want a different approach. Maybe direct action. Maybe withdrawal. Maybe waiting for collapse and rebuilding. But this framework won’t appeal to you.

If you share these assumptions, or at least want to test whether they still work, here’s how.

The Process

First: Figure out what actually happened. Don’t trust a single source, especially one that makes you feel good. Find sources from different angles. Note where they agree (probably true) and what each leaves out (probably spin). Ask who benefits from each version.

Second: Look beneath the surface. People aren’t just shouting positions. They have actual concerns driving those positions. And beneath those concerns are usually conditions — economic, historical, structural — that neither side fully controls. Understanding these layers doesn’t mean agreeing with everyone. It means seeing what’s actually happening.

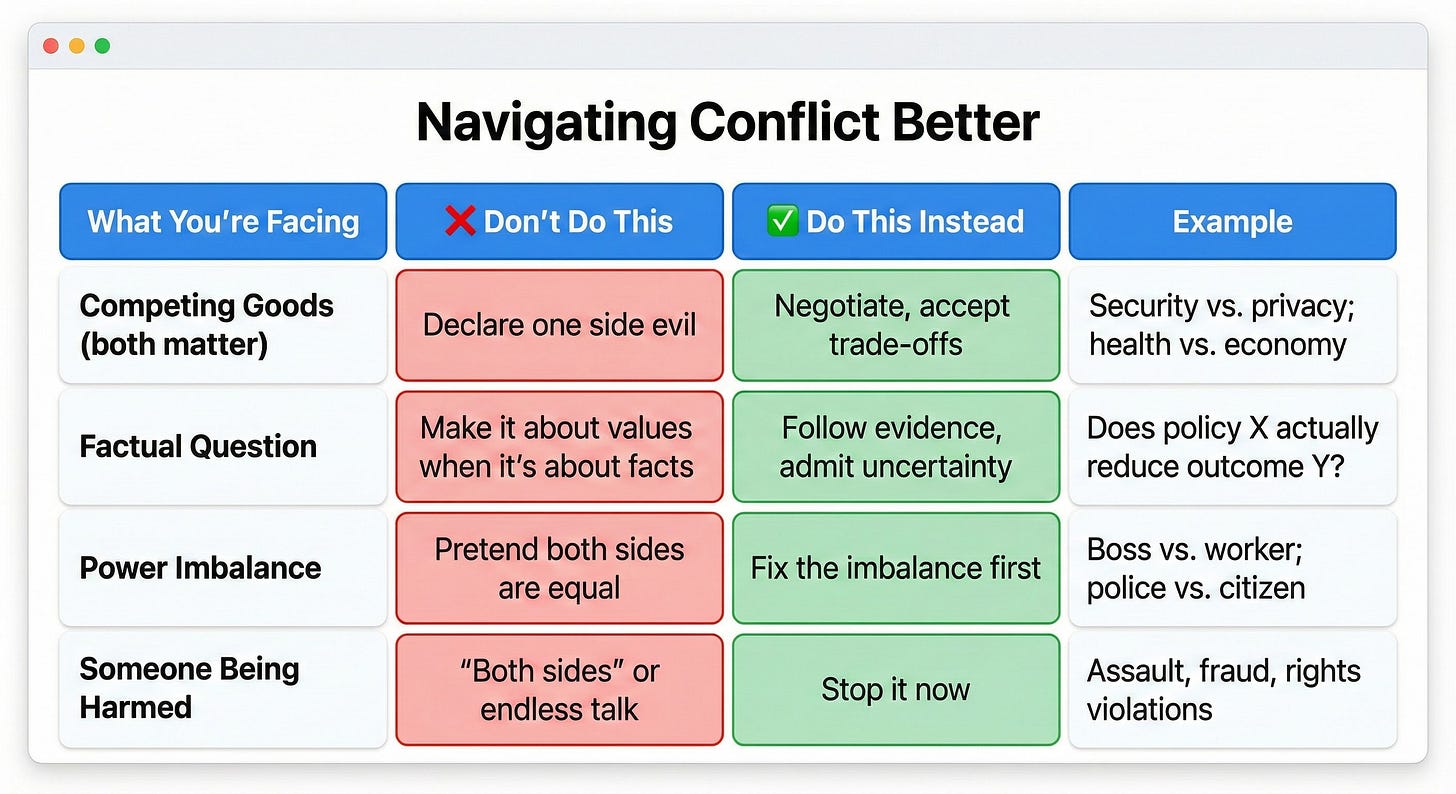

Third: Figure out what kind of fight this is. Is it competing goods that both matter? A factual question evidence can help settle? A power imbalance that needs fixing first? Or actual harm being done right now? Different kinds of conflicts need completely different responses.

Fourth: Respond appropriately. Don’t moralize empirical questions. Don’t negotiate moral violations. Match your response to what you’re actually facing.

Fifth: Test your own thinking. Can you explain the other side without making them sound stupid or evil? What might you be missing? What trade-offs does your position accept? What would change your mind?

Sixth: Decide if this is your fight. Not everything needs your input. Sometimes you need to understand more first. Sometimes it’s not your place. Know the difference.

Quick Pattern Recognition

Renewable energy and the grid:

What people say: “Green energy now!” vs. “Fossil fuels keep the lights on!”

What’s underneath: The progressive position focuses on climate crisis urgency, clean technology jobs, and future sustainability. The conservative position focuses on grid reliability, energy costs for working families, and economic disruption to fossil fuel communities.

What both sides miss: Solar and wind require massive grid upgrades and backup power because they’re intermittent. Natural gas plants currently provide that backup, meaning “renewable” energy still depends on fossil fuels. Battery storage at scale doesn’t exist yet at affordable prices. Nuclear could solve this but both sides have opposed it for decades — progressives over safety fears, conservatives over costs. Rural communities see their land taken for wind farms that power distant cities while they get nothing. Rare earth mineral mining for batteries happens in China under terrible conditions. The economic development in coal country was promised but rarely delivered.

What kind of fight: Competing goods (climate vs. affordability vs. reliability), empirical questions (what technology mix actually works?), power asymmetries (who pays transition costs?), some violations (if environmental damage or worker exploitation occurs).

The tribal positions — ”renewables solve everything” vs. “fossil fuels forever” — both miss that this is about managing extremely difficult trade-offs in energy systems where reliability, cost, environmental impact, and worker livelihoods all matter and can’t all be maximized simultaneously.

COVID shutdown policies:

What people say: “Follow the science and save lives” vs. “Lockdowns are tyranny”

What’s underneath: The pro-restriction position emphasized disease prevention, hospital capacity, collective responsibility, vulnerable populations. The anti-restriction position emphasized economic devastation, mental health costs, developmental harm to children, individual liberty.

What both sides miss: “The science” was genuinely uncertain, especially early on. Scientists disagreed about transmission, effectiveness of interventions, trade-offs. The laptop class could work from home; service workers couldn’t. Kids in stable homes with internet did okay; poor kids lost years of learning. Small businesses died while Amazon thrived. Public health focused on COVID deaths while mental health deaths, delayed cancer screenings, and childhood development got ignored. Restrictions worked differently in dense cities vs. rural areas but policies were often one-size-fits-all.

What kind of fight: Competing goods (health vs. economic survival vs. development vs. liberty), empirical questions (what interventions actually worked?), power asymmetries (who could weather shutdowns vs. who couldn’t), violations (when policies caused preventable harm either through disease spread or through restriction costs).

The tribal positions — ”lockdown skeptics don’t care about deaths” vs. “lockdown supporters don’t care about freedom” — both miss that genuine uncertainty plus legitimate competing concerns created impossible choices where every option had serious costs.

Notice: The people on both sides usually have real concerns, not just bad motives. And the conditions creating the conflict often aren’t either side’s fault. But hardened tribal positions prevent both sides from seeing the legitimate trade-offs and complexities.

The Reality Check Table

Save this. Use it when the next story hits:

A Deeper Look: Free Trade and Why Nobody Trusts Experts Anymore

Let’s work through an example that shows why this matters. Not a culture war issue, but something that still makes people furious: free trade.

What Actually Happened

From the 1990s forward, the U.S. dramatically lowered trade barriers. NAFTA in 1994, China joining WTO in 2001, other deals. The economic establishment from both parties including most economists, business leaders, and editorial boards promised this would be good for America.

And here’s the thing: they were right and they were wrong.

GDP grew. Prices for consumer goods dropped. Global poverty declined dramatically. Economists could point to aggregate benefits. The numbers worked.

But entire communities were hollowed out. Manufacturing jobs disappeared. Towns that had built lives around factories found those factories gone to Mexico or China. The people who lost jobs were told: “The economy overall is better. Look at the statistics. Here’s job retraining.”

Statistics aren’t people.

A guy in Ohio who spent 20 years on an assembly line making decent money doesn’t care that the aggregate GDP is up if he’s now working retail for half the pay and no benefits. His kid can’t afford college. His town’s Main Street is boarded up. The factory that was the community’s anchor and identity is gone.

When he says “free trade destroyed my community,” and economists respond with charts showing net benefits, he hears: “Your suffering doesn’t count.”

Looking Beneath the Surface

What free trade advocates saw: Comparative advantage creating mutual gains. Lower prices helping consumers, especially poor consumers. Global poverty reduction. Innovation and efficiency gains. The path to broader prosperity.

They weren’t lying. Those benefits were real.

What critics saw: Communities destroyed. Working-class jobs shipped overseas. Corporate profits up while wages stagnated. Economists and elites getting richer while working people got “job retraining” pamphlets. Promises that new jobs would replace old jobs, but the new jobs paid less and had no security.

They weren’t lying either. Those harms were real.

What caused this: Technological change, globalization, corporate decisions to maximize profits, inadequate policies to help displaced workers, underestimation of adjustment costs, China’s state-subsidized competition, automation happening alongside outsourcing, decades of declining worker power.

Neither side fully controlled these conditions. But the people who benefited acted like the costs didn’t matter or would magically resolve themselves.

What Kind of Fight This Is

Competing goods: Economic efficiency vs. community stability. Consumer prices vs. worker wages. Global poverty reduction vs. domestic working-class security. These are real tensions. You can’t maximize all of them simultaneously. Choices involve trade-offs.

Empirical questions: Do trade deals actually create net jobs? Over what timeframe? How much comes from trade vs. automation? What policies would help displaced workers? These have evidence-based answers, though contested.

Power asymmetries: Corporations had the power to move production; workers didn’t have the power to stop them. Executives captured the gains; workers bore the costs. Trade policy was made by people whose jobs would never be outsourced, for people whose jobs would be.

Actual harms: Specific plants closing without notice. Workers losing pensions. Communities losing tax base and descending into poverty and addiction. These weren’t “adjustment costs” — they were lives destroyed.

What the Right Response Looks Like

For the competing goods: Be honest that trade-offs exist. Cheaper consumer goods are valuable, especially for poor people. But community stability and working-class security are valuable too. Don’t pretend one is obviously more important. Different communities legitimately weight these differently.

For the empirical questions: Follow actual evidence on job loss, wage effects, policy effectiveness. Aggregate statistics matter, but so do distributional effects — who gains and who loses. Update beliefs when evidence comes in. Acknowledge uncertainty about complex economic effects.

For the power imbalances: Workers needed more power — better safety nets, genuine support for transitions, political representation in trade negotiations. You can’t have fair negotiation between unequal parties. The imbalance needed addressing first.

For the actual harms: Real people were being devastated. Not “we’ll handle it through adjustment,” but actual recognition and response. Job loss isn’t an Excel spreadsheet problem — it’s family trauma, community collapse, identity destruction.

What Went Wrong

The people who supported free trade focused on aggregate benefits while dismissing the human costs. When workers said “this is killing us,” the response was “but look at the GDP growth” or “you just need retraining.”

This created the backlash that gave us Trump, Bernie, and the collapse of the free-trade consensus. Not because free trade has no benefits, but because the people pushing it refused to acknowledge the trade-offs and the people bearing the costs.

The lesson: When you point to statistics while people are pointing to their ruined lives, they’ll eventually stop listening to you about everything. And they’ll be right not to trust you.

You can’t maintain trust in expertise if experts keep telling people their lived experience doesn’t count because the aggregate numbers look good.

When You Should Be Certain

This framework emphasizes nuance and humility. But some things warrant confidence:

Clear harms happening right now. When children are being hurt, when violence is occurring, when people are being systematically denied rights it makes sense to act first and deliberate later.

Well-established facts where expert consensus is strong. Climate change is real. Evolution happened. Vaccines work. The earth is round. You can be humble about remaining uncertainties while being confident about core realities.

Your own experience within its proper scope. You know what you’ve lived. A factory worker knows what job loss feels like. A cop knows what dangerous situations feel like. Trust your experience. But recognize it’s not the only experience, and that patterns beyond individual cases require evidence.

Basic moral principles properly applied. People deserve dignity. Power should be checked. Harm should be stopped. These principles are sound even when their application to specific cases requires careful judgment.

And sometimes, when the other side is actually lying. Not disagreeing. Not seeing things differently. Actually, knowingly spreading falsehoods. That happens. Distinguishing honest disagreement from bad-faith deception is hard but necessary.

The framework helps you know when to be certain and when to be humble. Not to doubt everything equally, but to calibrate appropriately.

When This Gets Really Hard

Here’s what happens when you try to use this in real life:

You can’t find honest perspectives from the other side. Your feed shows you what engages you. Your sources are filtered. When you look for opposing views, you get their worst people, not their best thinking.

You don’t have time. New crisis drops before you’ve processed the last one. Taking time to think means falling behind.

Admitting uncertainty costs you. “I don’t know” sounds weak. “It’s complicated” looks like cop-out. Changing your mind creates permanent record that’ll be used against you.

Politics is your identity now. Your neighborhood, job, friends, consumption, entertainment are all sorted by politics. It’s not one thing among many. It’s the thing that determines everything else.

You can’t actually evaluate most claims yourself. You have to trust experts. But which ones? Probably your side’s experts. Everyone’s epistemic situation is tribal now, even when you’re trying not to be.

This isn’t your personal failure. It’s what the environment does. Part 1 showed why judgment is hard. Now you feel it trying to use this framework.

When using these tools becomes nearly impossible despite genuine effort, the environment itself is broken. Individual virtue isn’t sufficient.

What About Bad Faith?

The framework assumes good-faith disagreement is possible. But what about when it’s not?

When people are deliberately spreading conspiracy theories? When they’re lying for profit or power? When bad-faith actors use the language of “legitimate concerns” to platform hatred?

Three responses:

First, distinguish honest disagreement from bad-faith deception. That’s hard but necessary. Someone who believes wrong things because they trust wrong sources is different from someone who knows better and lies anyway. The first deserves engagement. The second deserves exposure and opposition.

Second, you can’t engage everyone equally. Your time matters. Focus on people actually grappling with questions, not those performing for audiences or trolling. Sometimes the right response is ignoring, not engaging.

Third, some positions don’t deserve platforms. If someone’s “concern” is actually just racism, you don’t need to find the legitimate worry beneath it. Sometimes the answer is “no, that’s just racism.”

The framework isn’t infinitely generous. It’s for working through real disagreements, not for giving bigotry a hearing it doesn’t deserve.

What You Have Now

A process that works when conditions allow. A table to check when stories hit. Examples of it working and examples of what happens when people ignore the approach.

Use these tools where you can. Create space for pause when possible. Test your thinking. Engage appropriately.

But also pay attention to when it’s nearly impossible. That difficulty tells you something about whether we’re in normal political conflict or whether conditions for democratic judgment have fundamentally changed.

What’s Next

We’ve built a framework for judgment. But we already have one, tested over centuries: the Constitution itself.

The Constitution was designed for exactly this — people with fundamentally different values governing themselves together without destroying each other. It creates mechanisms for productive conflict: federalism, separation of powers, checks and balances, protected rights.

And remarkably, it contains capacity for self-correction. It was profoundly wrong about slavery, women’s exclusion, restricted participation. But it had mechanisms to recognize and fix those wrongs — amendments, evolving interpretation, protections for movements organizing for change.

Part 5 explores that constitutional framework: how it embodies these insights about conflict and judgment, how it’s proven it can correct profound errors, and why it’s struggling now.

Not because the design is wrong, but because conditions have changed and commitment to honoring it has weakened. When both sides treat constitutional restraint as unilateral disarmament, the mechanisms freeze.

The work isn’t finished. It’s just beginning.