Finding Coherence (Part 2)

A Guide to Political Judgment in Fractured Times (5-part series)

Part 2: The Case for Contestation

This is Part 2 of a five-part series. Part 1 introduced the problem: American politics has become incoherent, and we need better ways to engage disagreement—including with our own side.

There’s a powerful way of thinking about our current crisis: American democracy has always been contentious. The Founders disagreed vehemently. Lincoln’s election triggered secession. The Progressive Era was marked by bitter struggle. Civil rights required confrontation, not consensus.

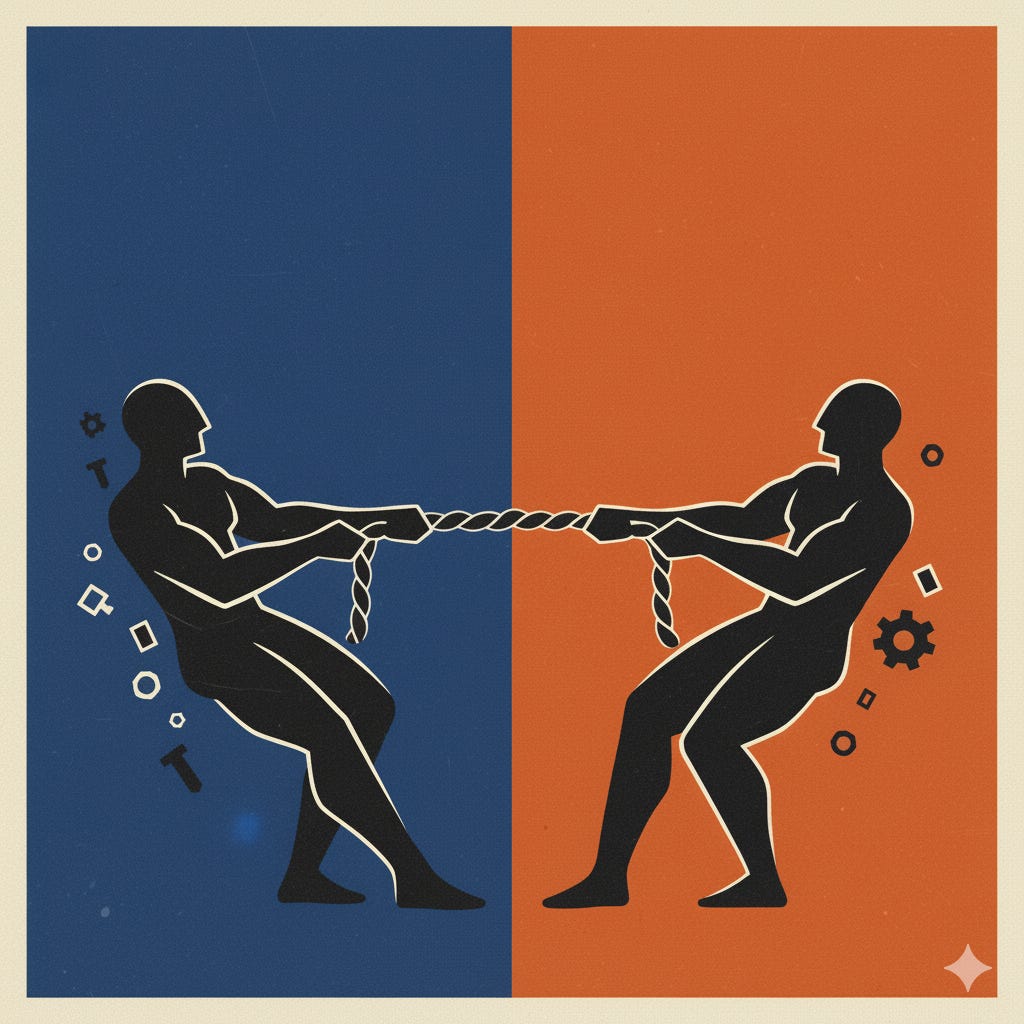

What we’re experiencing now isn’t democracy failing but democracy working as designed—managing inevitable disagreements through contestation rather than violence. The problem isn’t that we disagree; it’s that we’ve lost the capacity to disagree productively.

Permanent Tensions Between Competing Goods

Many of our deepest political disputes reflect genuine tensions between incompatible goods, not simple conflicts between right and wrong.

Individual liberty versus collective security. We want both freedom from government intrusion and protection from threats. But these values conflict in practice. Expand surveillance, you compromise privacy. Limit government power, you constrain its ability to prevent threats. After 9/11, we weighted security more heavily. During surveillance revelations, liberty concerns weighted more heavily. Different contexts require different balances.

The person emphasizing liberty isn’t ignoring real threats—they’re responding to danger of government overreach. The person emphasizing security isn’t dismissing freedom—they’re responding to the reality that insecurity makes liberty meaningless. Both see something real.

Economic freedom versus economic security. We value both entrepreneurial liberty and protection from destitution. But market freedom produces winners and losers, while robust social protections require constraining market outcomes. You can’t maximize both simultaneously.

The libertarian emphasizing market freedom isn’t heartless—they’re responding to efficiency and innovation that markets enable. The progressive emphasizing security isn’t ignoring incentives—they’re responding to reality that market outcomes often reflect luck more than merit, and that destitution is incompatible with dignity.

Cultural continuity versus cultural evolution. Communities need stable traditions providing meaning and identity. They also need to adapt to changing circumstances and include previously marginalized groups. Rapid change threatens continuity; defending tradition can perpetuate injustice.

The conservative defending tradition responds to real human needs for continuity and meaning. The progressive pushing evolution responds to exclusion and harm that traditional arrangements often imposed.

Notice the pattern: these aren’t problems with solutions. They’re permanent features of political life. Different situations require different balances. Any attempt to permanently “solve” these tensions by choosing one pole produces pathology.

Democracy as Ongoing Contestation

If many political disputes reflect permanent tensions, this suggests a specific understanding of democratic practice: not reaching consensus or eliminating disagreement, but ongoing negotiation through contestation.

Consider the progressive-conservative dynamic. Progressives push for change, responding to injustice in current arrangements. Conservatives defend tradition, responding to human need for continuity and danger that reform destroys valuable social knowledge.

Neither perspective is simply right or wrong. Progressive pressure without conservative resistance can dismantle valuable traditions recklessly. Conservative resistance without progressive pressure can perpetuate serious injustice indefinitely. This contentious dynamic between them produces more robust outcomes over time.

Democracy is less a search for final answers and more an ongoing argument that keeps different goods in play. Institutions including elections, legislatures, courts, a free press, and protected dissent provide outlets for these clashes so they don’t have to be settled by force. The goal isn’t to end the argument, but to keep it going under conditions where losers can survive to argue another day.

What This Perspective Promises

For many of our deepest conflicts, this framework works well. It avoids false hope that reasonable people should agree if they just talk enough — some disagreements reflect genuinely incompatible values, not failures of reasoning. It avoids cynical reduction of politics to pure power struggle. Shared commitments and mutual respect can coexist with vigorous contestation.

If democracy works through ongoing contestation among perspectives emphasizing different goods, then protecting dissent becomes crucial. You need robust protection for unpopular views and opposition voices.

Why This Matters for You

When someone disagrees with you politically, start by asking: What genuine problem or value might they be responding to? Not “how can I show they’re wrong?” but “what do they see that I might be missing?”

When you feel certain your side is entirely right, consider whether you’re treating a permanent tension as if it has a solution. Are you maximizing one value while ignoring the competing good your opponents emphasize?

When political opponents frustrate you, recognize they might be serving a democratic function in checking your excesses, identifying blind spots, and preventing pathologies that come from taking your preferred value to extremes.

This is a compelling vision. It explains why dismissing half the country feels wrong. They’re responding to real tensions and real problems, even when their solutions seem mistaken. It provides an alternative to both militant tribalism and squishy both-sidesism.

But, does this framework provide adequate guidance for ALL political conflicts? Are all disagreements truly constitutive tensions between competing goods? Or do some conflicts involve one side defending unjust power, denying established facts, or threatening the foundations that make democratic contestation possible?

These aren’t rhetorical questions. They’re genuine challenges we need to take seriously if we want to develop sound political judgment. That’s what we’ll explore in Part 3.